Introduction

1 The Nigerian university system is being ravaged by the menace of secret cults among the student population. Secret cult associations have infiltrated virtually all Nigerian institutions of higher learning and function to varying degrees of intensity in the various universities, including the military university. The southern universities have, however, dominated the discussions on student cultism in Nigeria. The Ogboni, which is a secret society, is found in all parts of Yorubaland (Fadipe, 1970). Hence, the location of the University of Ibadan at Ibadan, the heart of Yorubaland is sufficiently instructive.

2 The first student cult organization in Nigeria was registered in 1952 as a social-cultural club by the name of the National Association of Sea Dogs (Pyrates Confraternity). It was co-founded by Professor Wole Soyinka, the 1986 Nobel Laureate for literature, and six other students of Nigeria s premier university for reasons which represent the best of academic, soc,ial and cultural ideals students will fight for in any civilized society. These noble ideals center on the eradication of colonialism in all forms, promotion of respect for human dignity, and humanitarian activities, as well as the elimination of elitism and tribalism in society. The first twenty-five years or so of the existence of the University of Ibadan witnessed a vigorous pursuit of the ideals for which the Pyrates Confraternity, the only student cult association in the country at that time, was set up. At the time, the Confraternity was regarded with awe, although its role was neither violent nor destructive.

3 The emergence of a splinter group from the Pyrates Confraternity in the early 1970s, marked the beginning of a new orientation for future generations of Pyrates, as is being witnessed today. It also heralded the beginning of the proliferation of secret cult associations, not only in higher institutions of learning but also in some secondary schools across the country. At present, there are over 40 secret cult associations all over the country. The cultists, among other atrocities, kill, maim, rape, rob, steal, harass, intimidate, oppress, fight, kidnap, vandalize, repress, oppress, riot, assault, destroy, and poison - both innocent and rival cultists. In short, they symbolize a myriad of vices.

4. Hence, student cultism has become cancer to the general public, a demonic plague to the government, and a terrible nightmare to university administrators, lecturers, and the generality of students. If the goal of the university is to produce good citizens who will become the leaders of tomorrow, then students must be brought up in the best academic traditions, in an atmosphere of peace and harmony.

The problem

5 The major purpose of the study is to investigate the impact of secret cult organizations on university management. The study is also interested in collecting ideas and useful suggestions on how to eliminate student cultism at the University of Ibadan.

Theoretical framework

6A theoretical framework, which encompasses sociological, psychological, and management theories, was developed to explain the existence, growth patterns, and sustenance of the secret cult phenomenon in the Nigerian university system. 'Change' is a constant in human organizations, but the amount, direction, and time of change may not be foreknown. University administrators, therefore, must always be prepared to cope with change, recognize the cultural basis of student cultism, and adequately address both the latent and manifest factors promoting the existence of student cultism.

Review of related literature

7 The review of relevant literature indicates that the intensity of student cultism is not a function of whether the university is residential or off-campus, whether the university is state-owned or federal-owned, or even whether it is a university, polytechnic, or college of education. Student cultism is operated as a close-knit national network, despite the intercut rivalry and bloody clashes. So, the intensity of student cultism on a particular university campus is determined largely by the extent to which the university administration can deal effectively with both the internal cult members and the network at the same time.

Methodology

8. A case study was done, situated within the context of descriptive research, to determine the factors which have resulted in the growth and impact of student cultism at the University of Ibadan and how cults are being managed at the university. The study was conducted between January and June 1998. Both primary and secondary sources of data collection were employed; 697 respondents, including 580 students, were involved in the study.

Findings and discussion

9 The main findings of this study are as follows:

- There is a very wide gap between the orientation of the earliest cult organization, the Pyrate Confraternity, and the present-day cults. The change in the last fifty years has been systematic and progressively militant, with increasing use of violence in accordance with the rapid deterioration of the polity and decadence of society.

- Many secret cult organizations have been formed at the University of Ibadan. Some of them no longer exist. At the time of this research, about nine student cult organizations, including two new female associations, were active at the University of Ibadan. They include Pyrates, Buccaneers, Black Axe, Mafice, Bye, Black Cobra, Daughters of Jezebel, Pink Lady, and Viking.

- The respondents disclosed a wide range of reasons why they join secret cults at the University of Ibadan. These include the need for personal protection; to be able to secure employment after graduation; to secure power and prestige; to satisfy their curiosity about life; to become masters of their destinies; to make important contacts/connections; to escape punishment when they commit offenses; to access supernatural and magical powers.

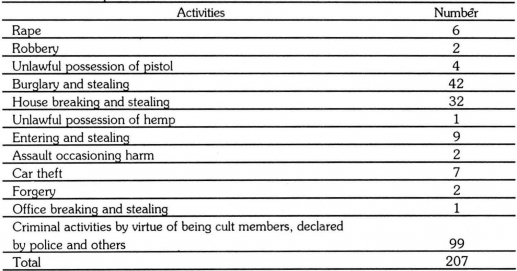

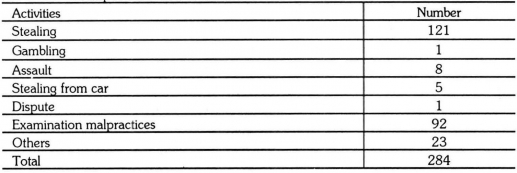

- The cult organizations recruit their members through inducement, coercion, advertisement, direct invitation, deceit, and peer influence.

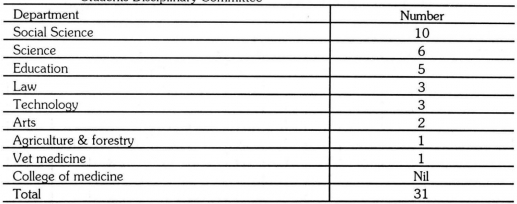

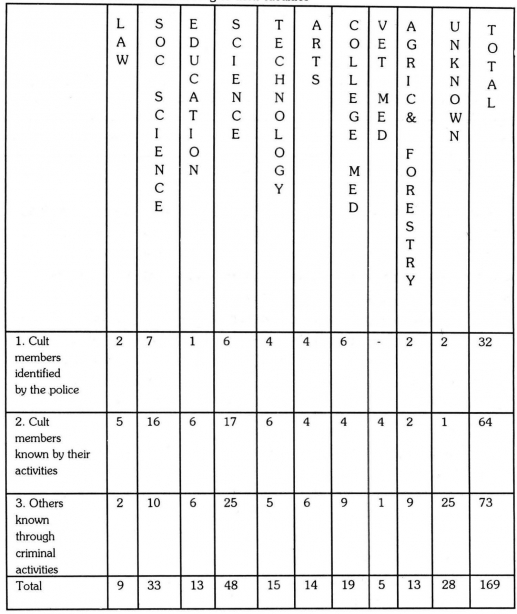

- No member of any secret cult interviewed was willing to volunteer information on their rules, regulations, procedures, rituals, and how and where their meetings were conducted.

- Cult membership is highly fluid on campus and is spread across various faculties and halls of residence. Cult members are also quite mobile, moving out of the halls where the management is hard on secret cult members, to halls where discipline is more relaxed.

- Cult organizations also operate off-campus branches (e.g., in Agbowo, a suburb opposite the university) which coordinate the activities of their members living off campus. Off-campus sites also serve as a major link between cult organizations at the University of Ibadan and their branches in other tertiary institutions. These houses/flats may also serve as a refuge for members.

- The secret cults at the University of Ibadan use threats and violence to enforce their rules. Most cult organizations recognize five levels, namely: individual, group, local, zonal, and national, depending on the scope and seriousness of the operation.

- Cult members are on the executive committees of most of the registered and prestigious socio-cultural organizations on campus, either as chairmen or ordinary members.

- Most of the respondents to our survey held a negative perception of cult members based on what they have heard and read about them, and not as a result of a direct experience of the cult members' activities at the University of Ibadan.

Impact of student cultism on university administration

10 Despite the negative image of secret cult organizations on the university campus, they are gradually permeating the social fabric of legitimate student organizations in search of power, influence, and affluence. And they are doing so quietly without being conspicuous. For example, it was gathered that the Awolowo Hall authorities wanted to organize their security force for the maintenance of discipline in the hall a few years ago. When they discovered that the first five students to volunteer for enrolment in the force were members of a secret cult, they canceled the project immediately. Another typical example was the 1993 Executive Committee of the Students' Union Government, in which five members out of eight (including the President), were members of secret cults. 11 It is important to state categorically, however, that neither the cult organizations nor cult members, individually or collectively, have ever directly influenced policy formulation and implementation at the University of Ibadan. Nevertheless, several instances were cited by respondents as evidence of the indirect ways by which cult organizations influence the implementation of policies in the university. A few examples will suffice:

- The frequent postponement of examination dates.

- The frequent shift since 1986 of the implementation of the cumulative grade point average (GPA) system.

- During this year's (1998) interhall football competition, Tedder Hall won the match over Bello Hall in the semi-finals. Bello Hall appealed to the Sports Council to declare it the winner because Tedder Hall fielded a non-student. In response, Tedder Hall assembled its cult members and paraded them to harass the Sports Council and Students' Affairs officials as a result of which the matter has not been decided one way or the other to date.

- Sometime in 1997, a well-advertised meeting involving both the student and graduate cultists was held at Samonda, Ibadan. The police raided the meeting and arrested some University of Ibadan cult members, among others. Apparently as a result, of pressure from the parents of the affected students, the university authority waded in to effect their release on the excuse that they were going to write the semester examination.

- The long delays, spanning several years, in the handling of secret cults are often cited as evidence that justice delayed is justice denied, and used to justify the indirect influence that secret cult organizations have on the university management.

12The general belief is that cult members get away with illegalities because they have godfathers. While cult members may get away with misdemeanors at the lower levels as often alleged, however, there is abundant evidence to show that they do not get away with serious offenses which catch the notice of higher authorities in the university, as the following section of this report reveals.

Impact of university management on student cults

13Although the banni13 Although persons from participating or belonging to secret societies had been entrenched in the 1979 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, secret cult organizations were not proscribed at the University of Ibadan until the 1984/85 session. Hitherto, the Pyrates Confraternity, the Eiye Confraternity, and the Buccaneers were officially registered and published in the Student's Information Handbook as social, cultural,l and political associations. In 1989, the government promulgated the Students Union Activities (Control and Regulations) Decree 47 of 1989 in order to curb the incidence of student cultism in institutions of higher learning in Nigeria. Section 2 of the Decree states that,

Where any society by whatever name called or known operating within the campus of a university or any institution of higher learning in Nigeria is pursuing activities which are:

Not in the interest of national security, public safety, public order, public morality or public health or

Illegal, inimical, destructive, or unlawful, the Governing Council, vice-chancellor, or any authority or person in control of the university or institution of higher learning, shall after investigation ng with respect thereto may proscribe any such society.

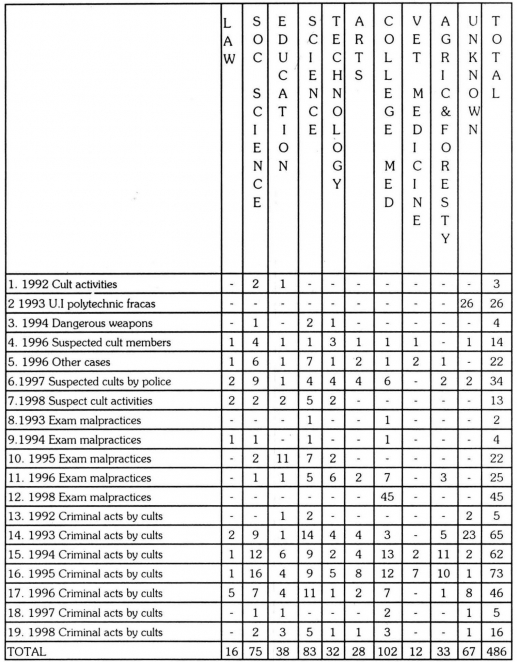

14 The decree also empowers the minister or his delegate to suspend, remove, withdraw, or expel any student from any institution of higher learning or similar institution whenever he thinks that public interest or public safety so demands. The student has a right of appeal within 28 days to the President of Nigeria, whose decision is final. The decree makes it an offense for students to engage or organize other students into any society proscribed by the same decree and also assigns a special court to try cases under the decree; the penalties include a fine of ₦50,000.00 or a five-year prison term or both.15Some eminent Nigerians see the decree as being high-handed on the part of government and liken it to attempting to kill an ant with a sled hammer; others believe that the decree might be counter-productive. Many more, however, are worried about the impact of the decree on university autonomy.16The first case of cult violence at the University of Ibadan was reported in February, 1991. It involved several Muslim students who were out in the early hours of the morning for prayers and were physically assaulted by a group of student cultists, apparently returning from an initiation ceremony. Consequently, a panel headed by Professor Balogun was set up to investigate the matter and this led to the eventual dismissal of some of the accused student cultists by the Students' Disciplinary Committee.17Again, there was a bloody clash between the Eiye Confraternity and the Buccaneers and the Black Axe, leading to the death of Emmanuel Okoroha, a 400 level physical and health education student of the university. Several suspected cult members, numbering about two hundred were arrested, investigations were conducted, suspects were duly tried and judgments were given in respect of each of the accused. A few were expelled; some were rusticated, and some were given a strong reprimand. Many were discharged. There is no doubt that the entire episode will be remembered for a very long time to come as the most bloody, the most celebrated, and the most protracted, having lasted over six years.18As a way of introducing an additional preventive control measure against the spread of student cultism, the university authority in April, 1995 not only reaffirmed its earlier ban on secret cults but also directed all its students to swear to an affidavit of undertaking in a high court of Nigeria not to belong to or support any secret cult organization (see appendix 1). Even though the cult-incited incidents of violence on the University of Ibadan campus have been infrequent, the widely held opinion confirmed by the university security reports is that there is an ever-increasing number of criminal activities on campus perpetrated by cult members. The most remarkable years were 1993 and 1994, with 34 and 32 reported cases of criminal activities, respectively. These criminal activities ranged from rape, illegal possession of firearms and Indian hemp, car theft, burglary, and forgery. Of all the misconduct offenses among the secret cult members, stealing is the most rampant, with 121 reported cases, representing about 25 percent of all offenses committed by the cult members between 1992 and June 1998. Other offenses reportedly committed by cult members include impersonation, gambling, intimidation, and examination malpractices. As in the case of criminal activities, the number of offenses emanating from misconduct, has considerably reduced since 1996 (see tables 1 and 2).19Between 1993 and June 1998, the Students' Disciplinary Committee tried several students for cult-related offenses such as membership of secret cults, illegal possession of firearms, dangerous weapons, and Indian hemp; involvement in the attack of students, assault on security men, illegal occupation of a university house, failure to appear before the investigation panel and refusal to appear before the Students' Disciplinary Committee. Accordingly, seven were expelled, three were rusticated, eleven were put on suspension, two were given a serious reprimand, four were warned, and four others were cleared of wrongdoing. It is noteworthy that ten of the offenders came from the faculty of the social sciences, while none were from the College of Medicine. Other faculties like Science had six, Education had five, Law and Technology had three each, Arts had two, while Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine had only one each (see tables 3 and 4). This analysis should not be interpreted to mean that there are no secret cult members among the students in the College of Medicine. Perhaps, the difference is that they have not been caught.

Table 1. Criminal activities suspected to have been perpetrated by cult members on the campus between December 1992 and 3rd June 1998

Zoom in Original (jpeg, 148k)Source: University of Ibadan Security Unit, 1998

Zoom in Original (jpeg, 148k)Source: University of Ibadan Security Unit, 1998

Table 2. Cases of misconduct suspected to have been perpetrated by cult members on the campus between December 1992 and June 1998

Zoom in Original (jpeg, 120k)Source: University of Ibadan Security Unit, 1998

Zoom in Original (jpeg, 120k)Source: University of Ibadan Security Unit, 1998

Table 3. Secret cult-related case concluded between January 1993 and June 1998 by the Students Disciplinary Committee

Table 3. Secret cult-related case concluded between January 1993 and June 1998 by the Students Disciplinary Committee

Zoom in Original (jpeg, 128k)Source: University of Ibadan Official Bulletin. (1993 - 1998)

20. From all indications, the incidence of student cultism on the University of Ibadan campus is low. As a matter of fact, most of the staff and students say that they do not feel the impact or the presence of secret cult organizations on campus; however, the media has given them the impression that cults are operating. Even the incidence of criminal offenses suspected to have been perpetrated by secret cult members on campus is, comparatively speaking, low in number, scope, and degree of viciousness when compared with what obtains in many other university campuses. Such is the evidence of the impact of the university administration on student cultism on campus. But how do they do it? Investigations reveal that the university attacks the problem from at least ten different angles which are enumerated below:

- The use of university tradition and culture anchored on excellence and character

- The use of the Students’ Disciplinary Committee

- The use of the university security operatives

- The use of the University Surveillance Corps

- The use of the University Parents’ Forum

- The use of the police

- The use of informants

- The use of religious activities

- The use of enlightenment campaigns among the students

- The use of effective administrative controls

21 Nevertheless, there is still room for improvement. These issues will form the basis of the discussion that follows in the concluding part of this report.

Table 4. Cult members according to their faculties

Zoom in Original (jpeg, 264k)Source: University of Ibadan Security Unit, 1998.22

Zoom in Original (jpeg, 264k)Source: University of Ibadan Security Unit, 1998.22

N.B. Unknown probably refers to non-students of the University of Ibadan who may be members of the secret cult network from other institutions learning

Conclusion and recommendations

23 Student cult organizations in institutions of higher learning in Nigeria are perceived as gangs of violence-prone terrorists and destruction-oriented thugs that are dreaded by everybody, including the authorities. The apparent helplessness of most university authorities to deal effectively with student cults originates from Decree 47 of 1989 which regards membership of a secret cult as a criminal offense and empowers only the president of Nigeria or the Minister of Education to expel suspected cult members. In addition, the exclusion of religious and cultural organizations as potential cult organizations by Constitutional definition, coupled with the oath of secrecy often undertaken by student cult members, make it extremely difficult for university authorities to prove beyond reasonable doubt that a suspect is truly a cult member. In the second place, the question of secret cult membership as a criminal offense not only takes the jurisdiction out of the campus to the police and the court, but it also delays the administration of justice considering the length of time it would take the police to investigate and the Courts, through series of adjournments, to deliver judgment. In third place, both the criminal nature of the offense and the empowerment of only the president of Nigeria or the minister of education by the law to expel student cultists, not only shifts student fear and respect of the authorities outside the university (police, court, military, politicians, top civil servants, etc,.), but more importantly, it seriously undermines discipline, academic freedom and, university autonomy.24The earliest campus confraternities (1952) had no clear ideology or philosophy nor was there a properly articulated statement of purpose. This appears deliberate to give future generations of Pyrates the freedom to direct the affairs of the organization following the challenges of their rapidly changing environment.25As The larger society became more militant, more violent, and more oppressive, and the student cult organizations followed suit. The existence of formidable associations of the graduates of campus cults (e.g., Pyrates, Buccaneers, Eiye, etc.) in responsible positions in all spheres of national life, and the strong bond of friendship and esprit de corps among them, are sufficient proof that campus cults are not necessarily delinquent gangs or ordinary clubs. Therefore, the role of the mass media in drawing the attention of the public to the problem of student cultism, molding, and mobilizing public opinion against cults has to be more objectively re-examined. There are three other reasons why this is necessary. Firstly, the mass media reports on student cultism are often exaggerated, fragmented, and distorted although they usually contain an element of truth. Secondly, despite the mounting adverse publicity against it, student cultism has proliferated, and become more influential on our university campuses. Thirdly, the focus of the media on the campus cults is like trying to kill the child after an unsuccessful attempt on the mother, who is capable of multiplying herself severalfold. The media is probably fighting a war that it may never win. Its abysmal failure in its massive campaign against the mother cults in society during the 1970s is a good case in point. Presently, the mother cults are waxing stronger and stronger in the larger society. This is not to say that campus cults are desirable or a necessary evil, but that in motivated a meaningful solution to the present menace of campus cults we may have to revisit the cultural origins of secret cults at institutions of higher learning. There is no doubt that the University of Ibadan has demonstrated the managerial capacity to minimize the incidence of student cultism on campus (see table 5).26As a matter of fact, the so-called Mosso-called us of the cult organizations namely the Pyrates, Buccaneers and Eiye confraternities had operated openly as registered associations without giving the University of Ibadan authorities any headache in the early 1980s, before they were banned. The tacit encouragement given by the authorities to prayer meetings and services by religious associations in the Student Union building and halls of residence, in particular, has helped to reduce student cultism on campus. So also is the unwritten rule given to hall wardens by the university management to eject from the hall or refuse to accommodate in the hall any suspected cult member. In the light of these findings, the following recommendations are made:

- The capacity of the basic facilities such as the library, hostels, sporting facilities, recreation facilities, classrooms, reading rooms, etc. were originally designed in the sixties to accommodate 4 000 students; these have become grossly inadequate to the needs of a student body of over 10,000. The students may find themselves unable to manage their leisure time which leaves them open to exploitation by secret cults. Therefore, there is a need to improvn these facilities considerably in tove students the tools to fulfill a healthy, moral, and academic obligation.

- The university admission process lasts for about six months every year. This long period and some inherent weaknesses in the admission process are usually exploited by the cult members who recruit some of their members during this period by getting them admitted into the university in one way or the other. To remedy the situation, the period of admission has to be shortened, and all admissions must be done in a conference and finalized before resumption.

- The existing halls of residence only accommodate one-third of the current student population. As a result, fresh students, especially those who come from far away or do not know their way around spend their first few days or even weeks sleeping in classrooms, the porters' lod,ge or corridors. At this juncture, the cult members intervene, offer them hospitality, get them accommodation and eventually recruit them into their organizations. To stop this practice, fresh students should be allocated rooms in the halls of residence before resumption.

- Academic programs in the university should be strengthened in order to keep the students intellectually engaged in their studies, with no spare time for cult activities. This could be done through the reactivation of seminars, tutorials, projects, assignments, etc., to the students.

- The structures, facilities, and organizations which used to provide and promote extracurricular activities in the university have either collapsed or disappeared completely. There are very few voluntary games, sporting activities, book clubs, debates, drama shows, film shows, public lectures, symposia, educational excursions, etc., aimed at engaging students' free time. The absence of wholesome social activities gives room for student cultism to take up the gap. The long-term solution is in the reactivation of the relevant structures, faculties, and bodies such as social clubs and, sporting competitions; the short-term solution is to shift the burden on the academic departments and halls of residence, give them a re-orientation and provide logistic and administrative support services through the Students’ Affairs Division.

- Faculties are almost completely ignorant of the activities of secret cult members on the campus. While this may be good, in terms of preventive measures, this is not good. Faculty staff and students should be mobilized and kept abreast of university campaigns against cultism.

- Universities should be empowered, without external interference, to handle the problem of cultism on their campuses. As the University of Ibadan has shown, each university could develop the administrative capacity to reduce the presence of secret cults on their campuses. Therefore, the vice chancellors of Nigerian universities should see to the repeal of Decree 47 of 1989 which makes membership in campus cults a criminal offense.

- Given the cultural origin of student cultism, and its proliferation, despite various bans and adverse publicity, it is hereby recommended that the ban be lifted on secret cult organizations and their activities regulated by the university authorities. This arrangement had worked well for more than three out of five decades of the existence of the University of Ibadan. There is no reason why it should not work again.

Table 5. Criminal activities suspected to have been perpetrated by cults between December 1992 and 31st July 1998 at the University of Ibadan

Zoom in Original (jpeg, 554k)Source: University of Ibadan Security Unit, 1998.27

Zoom in Original (jpeg, 554k)Source: University of Ibadan Security Unit, 1998.27

N.B. Unknown probably refers to non-students of the University of Ibadan who may be members of the secret cult network from other institutions of higher learning.

Policy implications

- The University of Ibadan's experience with the off-campus accommodation in Agbowo, etc., as well as the experiences of the Lagos State University, Ogun State University, and, Ondo State University, just to mention a few, has shown convincingly that non-residential policy is not the solution or even a solution to student cultism. Rather, it makes it difficult for the university authority to monitor and design effective strategies for controlling the activities of secret cult members. Therefore, it is suggested that the lodgings office should be actively involved in securing hostel accommodation rather than individual apartments for students living off campus.

- Hall management policies should be re-evaluated to strengthen hall leadership, internal policies, and politics, to be able to control the rooms and weed out the undesirable elements, especially the secret cult members and any non-university students.

- Quota policy on admission brings into the university some students who are academically weak or not serious enough to cope with the rigors of origorsrsity education; such students are more vulnerable to enticements by secret cult organizations. Therefore, the university has to be more careful in its use of the quota system so naturally that it does not undermine the academic standards for which the University of Ibadan is well known.

- The policy on the transfer of students should be tightened to include an interview of a candidate to avoid admitting student cultists expelled from other universities. The National University Commission should initiate a policy whereby the list of cult members identified or expelled in each university is sent to all other universities through the committee of vice-chancellors.

- The immediate implementation of the cumulative grade point average (CGPA) policy will force students to spend most of their time on academic activities and thus reduce the incidence of student cultism

- The university should popularize and enforce the policies on academic progression from one level to another. This will make most students, especially cult members, sip and devote more of their time to academics instead of cultism.

- The university should institute a policy which gutguaranteescommodation in halls of residence to all its fresh students.

- The university should develop a policy of providing a well-articulated and comprehensive programme of guidance and counseling to identified or suspected cult members. This program will enable the university to trace the students to their homes and develop a deeper understanding of the problems of cultism on campus and help in rere-molding the character of such students.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

References

Abati, R. 1994. The cults, the kids, the occult. The Guardian (4 March) p. 19.

Abiodun, Adeniyi. 1997. Government may adopt Abu's reports on culture t. The Guardian (11 August).

Adedoja, Taoheed A. 1997. Provost on how to stem cultism. Sunday Tribune (10 August) p.3.

Adegbenro, Adebanjo 1998. Apostles of the Apocalypse. Tell Magazine (2 March).

Ademolekun, N.K. 1995. Secret societies in Nigerian universities. Daily Sketch (11 July) p.5.

Adeola, I.O.A. 1997. Secret cults in Nigerian universities of learning: A periscope appraisal.

In: Readings on Campus Secret Cults. O.A. Ogunbameru, ed., Kintel Publishing House, Ile-Ife, p. 51-69.

Adeoye, Segun. 1997. Decree on cult coming. The Guardian (30 July) p. 3.

Aderinto Adeyinka and A. Adebanyo Oyebode. 1997. The phenomenon of secret cults in Nigerian tertiary institutions, origin precipitating factors and probable solutions. Journal of Health and Social Issues (1).

Aderinto, Adeyinka. 1994. Student unrest and urban violence in Africa, p. 233-238. In: Urban Management & Urban Violence in Africa, Vol. 2, I.O. Albert, J. Adisa, T Agbola, and G. Hérault, eds., Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique, Ibadan.

Agbese, Dan. 1994. Life’s Cruel Joke. Newswatch (28 March).

Alafo, M.O.A. 1997. Secret cults impediment to social economic development. New Nigerian (6 January) p. 5.

Amaotule, Longinus. 1997. Don advocates stiffer penalties for cult members. The Guardian (5 December).

Ambrose Akor & Ors. 1994. A malignant cult epidemic. The Guardian on Sunday (13 March).

Ayoola., Banji. 1997« Survivors of hellish cults. Guardian on Sunday (6 July) p. Bl & B3.

Ayoola, Banji. 1997. Stories from hell. Guardian on Sunday (6 July p. Bl & B3).

Banjo, Ayo 1997. It is too late to kick out cultism from the university. Guardian on Sunday (13 July) p. 49.

Carrillage, Victor A. 1991.The Secret of secret cults. Nigerian Tribune (15 June) p. 5.

Daminabo, M. 1991. Campus Cults and Student Unionism. The Guardian (7 May) p. 9.

Erickson, E. H. 1968. Identity: Youth and Crisis. W. W. Norton Publishers, New York.

Fafunwa, Babs. 1990. Cult culture in varsities. Nigerian Tribune (15 June) p. 5.

Fadipe, N. A. 1970. The Sociology of the Yoruba Ibadan University Press, Ibadan.

Ifaturoti, T. O. 1994. Delinquent subculture and violence in Nigerian universities, pp. 149-159. In: Urban Management and Urban Violence in Africa. Vol 2. I.O. Albert, J. Adisa, T Agbola, and G. Hérault, eds., Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique, Ibadan. Igboanugo, Sunny. 1997. Buhari urges tougher measure on cultism. (1 September) p. 3.

Ige, Tayo. 1997. Ogboni vs bishop: Why the church can’t enforce a ban on secret cults. TheNews (24 November) pp. 12-17.

Makinde, M.A. 1997. The evil of secret societies. Daily Sketch (26 August).

Mellanby, K. 1958. The bush of Nigerian's university. Methuen and Co. London, p. 269.

Obari, Joseph Ollori. 1997. Uniport expels 30 students for cult activities. Guardian (8 May) p. 5.

Obari, Joseph Ollori. 1998. Rivers raise task force on cultism. Guardian (20 January) p. 4.

Ogunmeru, O. A. 1997. Reading on Campus Secret Cults. Kimtel Publishing House, Ile-Ife,

p. 10jo, J. D. 1995. Students Unrest in Nigerian Universities. A legal Historical approach. Spectrum Books, Ibadan and Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique, p. 109.

Omosule, S. 1994. Cults and magical approach to solution. Nigerian Tribune (February 24) p. 8.

Oyekanmi, Rotimi. 1997. Police discover gun cult insignia in UNILAG Halls. Guardian, (10 September) p. 1.

Sanda, Muyiwa. 1992. Managing Nigerian University. Spectrum Books, Ibadan, p. 91.

Sogbola, G. 1997. Secret cults are a threat to peace. Sunday Tribune (28 August) p. 5.

Sotunde, Iyabo.1997. V. C. advises matriculation students to shun cults. Guardian (11 August).

Udeni, A. 1994. Terrorism on campus. Vanguard (19 March) p. 8-10.

University of Ibadan. 1996. Student Information Handbook, The Students Affairs Division, University of Ibadan, p. 152.

Newspapers and Serials

Editorial Comment. 1997. Closure ocult-riddenen institution. Guardian (11 July) p. 12.

Editorial Comment. 1997. Security on our campuses. Guardian (4 July) p. 12.

Editorial Comment. 1997. Campus cults: Not a matter for decrees. Guardian (6 August) p. 18.

Editorial Comment. 1997. Dangers secret societies pose to Nigeria unity. Nigerian Herald (30 September).

Editorial Comment. 1997. Government advised to extend anti-cult battle to school: Guardian (18 July).

Editorial Comment. 1997. the Threat of cults. Guardian (26 October).

Editorial Comment 1994. Daily Times (22 March).

Newswatch various issues (1994).

Newswatch (28 April 1994).

Sunday Sketch (15 July 1990).

Sunday Times (21 April 1991).

The Guardian (28 December 1993).

The Guardian on Sunday (20 March 1994).

The Sketch (7 June 1991).